Exhibition

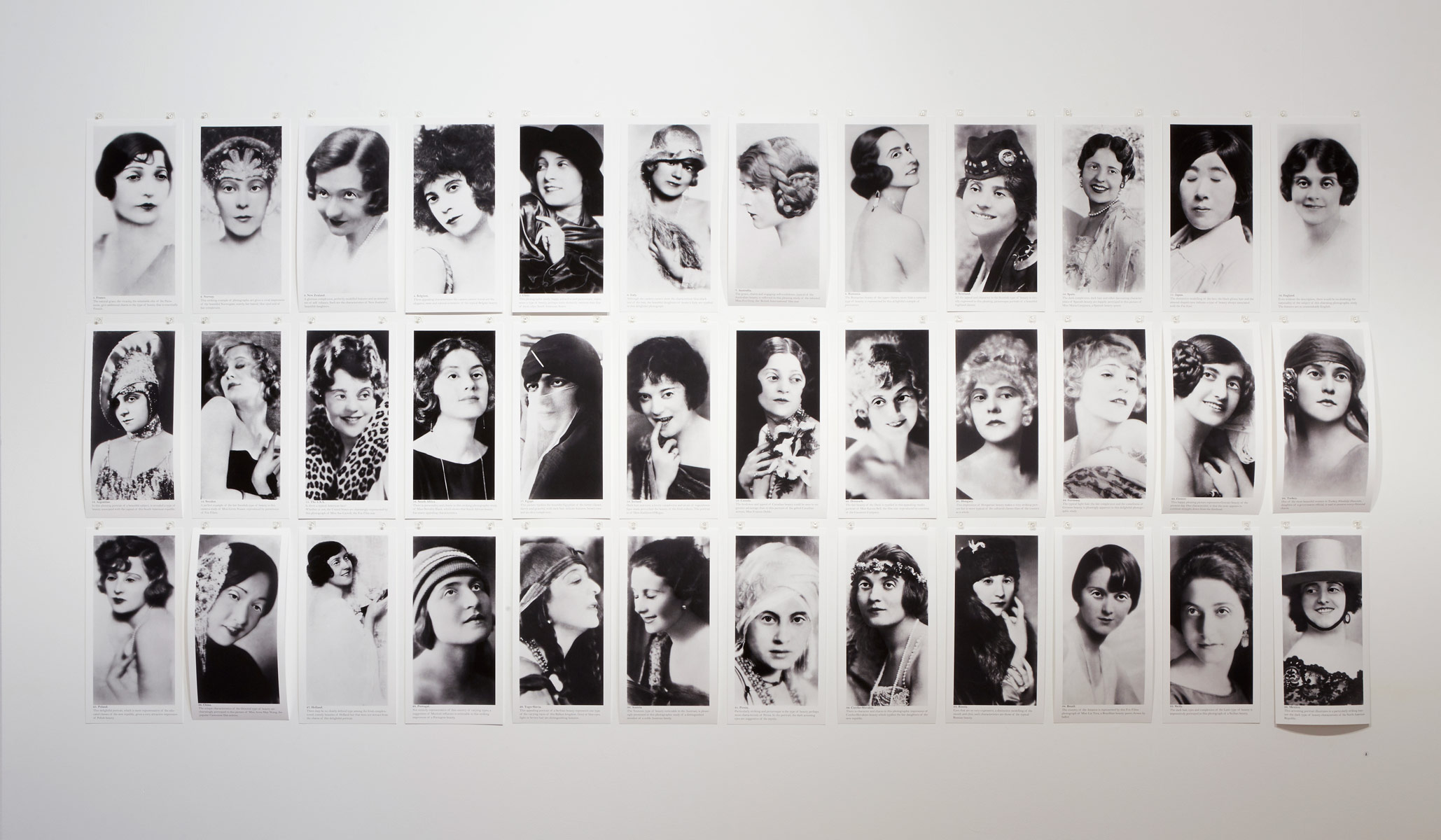

Cherine Fahd presents her latest body of work, National Types of Beauty, a series of subversive portraits developed from a set of English cigarette cards produced in 1928 depicting images and loaded texts descriptive of the national types of female beauty…

Exhibition Opening: Wednesday 3 May from 6-8pm.

The photographic portrait is the focus and the inherent challenge of Cherine Fahd’s art. Her self-portraits, where the photo-artist ironically reveals only selected bodily features as in her Camouflage series or Plinth Piece body of work in which she takes on the appearance of sculpture, all test the paradox of hiding from the camera. The concept and enigma of the self-portrait she also addressed in her recent Ph.D. Hiding from the Camera for the Camera: the photographer-subject in self portraiture.

Her latest body of work, National Types of Beauty is similarly subversive. It is developed from a set of English cigarette cards produced in 1928 depicting images and loaded texts descriptive of the national types of female beauty and is presciently topical in the contemporary climate of escalating reports of ethnic, gender and religious typing and discrimination.

Cherine Fahd bought a single card, Japan, at an Australian market ninety years on from its original publication date. Intrigued by the

Orientalist stereotypical fantasy and colonial misogynist eye behind the series and its accompanying texts, the artist sought out a set of the 36 tiny cards aimed at a male audience (they usually depicted sports heroes, aeroplanes or cars) and distributed by the British tobacco company, Major Drapkin & Co.

Their racial classifications revealed notably no coloured women and blatant ‘Colonialist’ class distinction and aspirations in the captions on the back of the cards extolling an: “Egyptian – of the better classes”; “…from a noble Austrian family”; “… daughter of a government official” and the Polish ‘National Beauty’ being from the “… educated classes”: a kind of ‘Country Life Deb’ series in miniature for private acquisition and delectation of the everyman…

Working with a premise of the eyes as the place of principal engagement Cherine Fahd has responded with her own subversive suite of images, National Types of Beauty (2017). The artist

scanned the original cards and took multiple self-portraits in her studio, posed with her eyes in emulation of the direction faced and the level of focus of the individual so-called ‘Types’ in the cigarette cards. She substituted her own eyes into every portrait, brought the texts onto front and centre printed below each portrait, and up-sized the images to human scale.

This series is the distaff side of You look like a…2016-2017, also currently in production. The binding tenet for both projects is racial classification. You look like a… is a series of large portraits of dark-haired bearded males in response to Western stereotyping of ‘Arab appearance’. It is to be exhibited with a series of smaller scale conflated portraits combining the female artist’s self-portrait of the upper portion of her face with the bearded lower area of the male. The images are to be published in tandem with the artist’s Shadowing Portraits series and an essay by Blair French as a book version appositely titled A Portrait is a Puzzle.

Barbara Dowse

Curator

The artist’s own words reveal her insights and motivations:

In the early 1900s tobacco companies produced cigarette cards in order to strengthen cigarette packets and to advertise their brand. Major Drapkin and Co. was one such company based in London. Cigarette cards were miniature trading cards used to entice smokers to collect and exchange them. Judging by the subject of most cigarette cards, men were their number one consumers. Many of the cards were of soldiers, planes or sporting heroes, and smokers were encouraged to collect the whole set.

National Types of Beauty is one such set of trade cards. However, it is unusual in its representation of women. National Types of Beauty was issued in 1928. It consists of 36 portraits of women who according to the British colonial eye exemplify the beauty of the named country. On the front of each card a black and white photograph depicts the apparent national type of beauty of the said country. On the back, the women are described according to their facial appearance, their colouring, their class, their level of education, and whom they belong to (whose daughter they are). What struck me about the descriptions were not only the way the women merely existed as a classified specimen but the way each race is described and depicted according to colonial desires of the era. For instance, the card for Egypt presents a woman who fulfils the Orientalist fantasy of wearing veils that are less fearsome burka and more Cleveland street belly dancer.

I have been collecting the National Types of Beauty set since 2010. This set while appealing to my interest in photography also troubled me in its colonial representation of race and of women. The text on the back, which I have reproduced in my version, has condescension to it and when I read it I find I have to put on a pompous imperial voice. Little details were ironic when I studied the set closely. Incredibly, white women represented Australia and South Africa. In fact there is not one single woman who isn’t white in the entire set. The Australian woman is declared to be a British actress and ironically the name of the South African lady is Miss Dorothy Black. New Zealand has no connection to its Maori beauty and former countries such as ‘Yugo-Slavia’ are represented whilst Iran is still called Persia.

I held onto this set for seven years not knowing what to do with them. They hung on my studio wall prompting action. Last year I began making large portraits of men with beards (‘You Look Like a…’ 2016-2017). The focus of this project is racial appearance, the darkness of my subjects indicating an Arabic-ness and the politicised nature of being or appearing Arabic in the West. Looking at these portraits as a typology of sorts prompted my reworking of the National Types of Beauty as they began to inform each other on my studio wall. What they obviously have in common is a typology according to racial appearance and a classification that is fundamentally false.

My reworking of this archive carries the same name, ‘National Types of Beauty’ (2017). In this adaptation the portraits are altered and share one common feature – each of the ‘beauties’ wears my eyes almost imperceptibly. This act for me is simple. It undoes the colonial gaze and the attempt to categorise race and women. My eyes fit better on some women then others and in some they are closed. These portraits also recall my previous attempts in ‘Plinth Piece’ (2014) and ‘Shadowing Portraits’ (2015-2016) to take on the appearance of other things, a sculpture or another person. In these portraits I become fused and enmeshed in these historical women’s faces. Looking out as a knowing eye, critiquing, questioning and quietly challenging.

Cherine Fahd, 2017